Project / Published on February 22, 2021

Share to

BUILDING ON MEMORIES

RETHINKING THE QUÉBÉCOIS HOUSE

Interviews with Gilles Saucier, architect

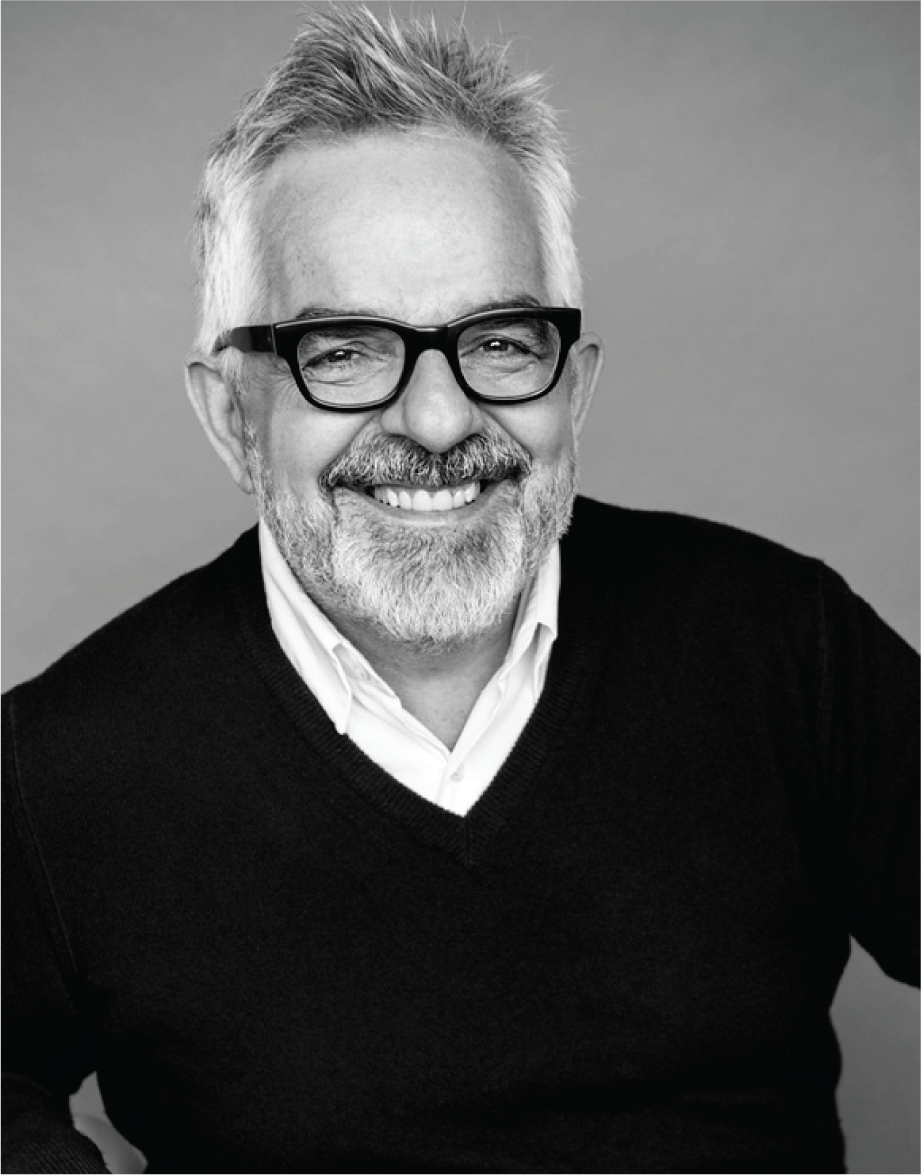

Architect Gilles Saucier, co-founder of Saucier + Perrotte Architectes, has never been a stranger to major projects such as the Guggenheim Museum in Helsinki or Usine C and the Montreal Soccer Stadium.

However, rebuilding the house of his then eighty-year-old parents in 2009 was an unprecedented challenge for him that significantly nourished his architectural practice.

How does one build on memories? How can we take a fresh look at an environment without the risk of uprooting those who have lived there for forty years?

Met by the magazine INTÉRIEURS at the time, the architect presented us with a deeply personal and simply timeless project. So timeless that twelve years later, the project and the words are still relevant.

The result, two interviews full of candour which, according to the principal concerned, will have had quite a beef effect!

Discover the conceptual approach behind the reconstruction of his parents’ house. A project that led Saucier not only to mend his conception of architecture, but also to consider a new version of the traditional Quebec house: simple, open and authentic.

by Alain Hochereau, published in INTÉRIEURS 46 + 48, 2009.

Photos: Olivier Blouin, Gilles Saucier, Saucier + Perrotte Architects.

INT: What was left of the house after the fire?

GS : Nothing but the foundations. On the other hand, the landscape had remained intact. When we moved in,in 1967, there were only three centennial maple trees. All the rest, we planted ourselves.

Today, the trees have matured and seem to belong entirely to the place, as if they had always been there. One could say my family built the landscape.

INT: What was particularly challenging about rebuilding your parents’ house?

GS : Building a house implies offering a specific viewpoint upon its environment. It means that, depending upon where you are inside the house, you’re going to perceive this or that aspect of the landscape according to the number, size and orientation of the windows, for instance.

But what do you do with the existing memories? My responsibility was to make my family feel at home in it, and it therefore had to preserve the perceptions they had developed in that environment. When you are eighty, you body of memories and perceptions sums up the soul of a whole life.

INT: Were you then going to reproduce the previous use in order to preserve your parents’ memories?

GS : No. My aim was to enhance the point of view that had been developed through those forty years. The river and the trees were always part of my parents’ perception of their home; however, the openings in the old house did not allow them to see them from within, completely. There were many things my parents could not see. So I offered them a rediscovery of their environment, based upon the landscape aspects that had become more significant through the years.

What was important to them?

By sorting out their memories, I was able to identify priorities, and thus, reorganize the viewpoints provided by the house, onto its environment.

INT: Can we see a little of you in this house?

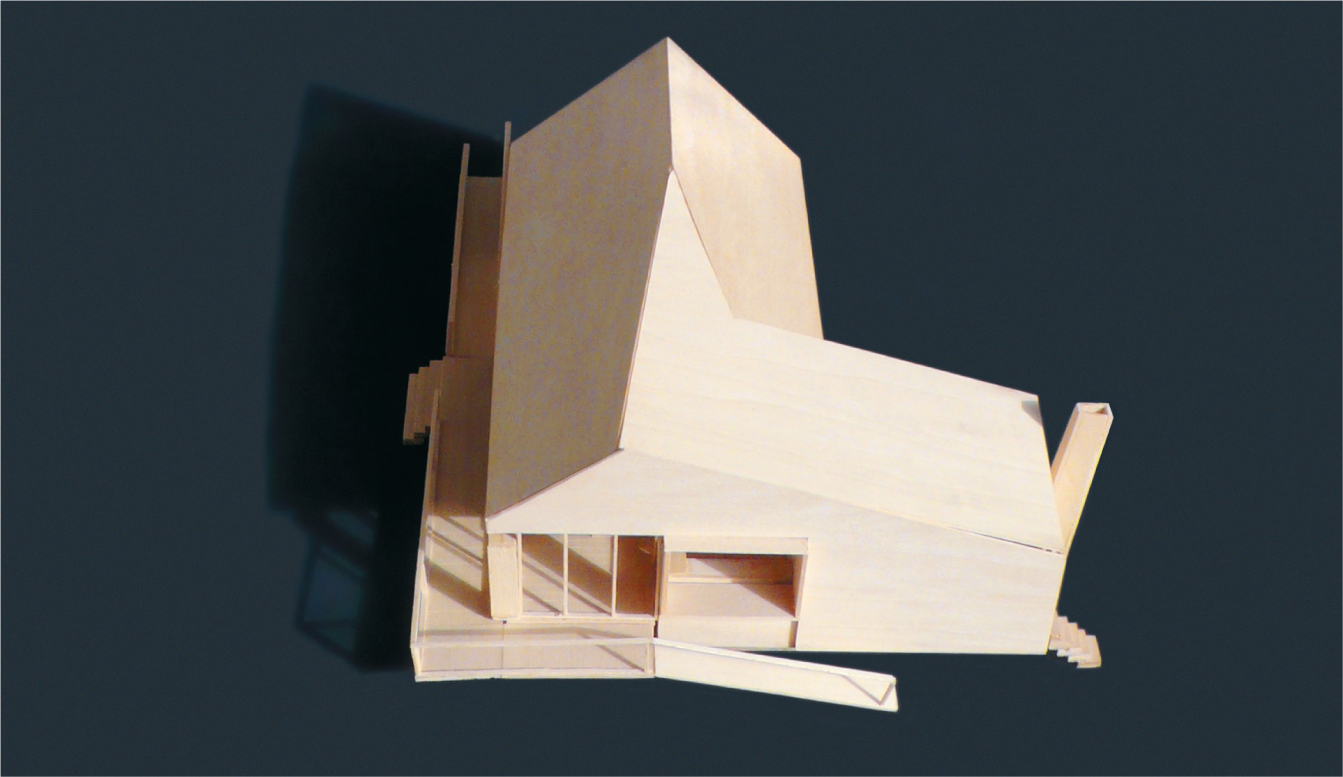

GS : Obviously! My rereading of the landscape was shaped by my experience as an architect. The original house dates back to 1840, and it had traditional architecture with a gable roof, a gallery, and a summer kitchen.

I wanted to revisit it by achieving a synthesis between family memories, the Québecois traditional house and elements of typical landscapes from the Bas-du-Fleuve area. This is why it has a “worn out brown barn” feel to it )as are many found in the area).

Its asymmetry is an allusion to the tiny lopsided bridge my father and I built across the river down there, when I was little.

And the black exterior? A wink to the fire (smiling)…

INT: Did you take your parents’ age into account when making the house plans?

GS : Absolutely! It is even laid out for easy circulation in a wheelchair. The house is built on one single floor and has a huge living space opening onto the kitchen area.

While today everything seems to be shrinking, the interior architecture creates a feeling of largeness – even though the dimensions are quite practical on a human scale.

I did not want this to look like an old folks centre. So I took special care to incorporate the house into the environment my parents are so attached to: the fruit trees, the vegetable garden… The access ramps for wheelchairs are very discreet, as they prolong the galleries circling the house. This is the way houses should be built, not from a purely functional perspective, but to preserve the link between the people and their environment.

INT: What did you get out of the experience?

GS : An awful lot! First of all, t was an act of love. You rarely have the opportunity to reassure your parents while getting them to understand what you do for a living.

This house has shown them are about my professional activity then any magazine article ever could. They become personally aware of it.

Through my own language, I helped them contact their memories. By the same token, putting my practice into words has nurtured it and made it grow. As a result, I feel more enlightened when it comes to choosing the most significant elements in the environment for a project. I also feel I know more about why I work as an architect. My actual aim is to help people reconnect themselves with their environment. For that purpose, the architect must be able to reinterpret people’s emotions with eloquence and also great humility.

INT: You mentioned that building this house has helped you better fathom why you have become an architect…

GS: In a way, yes. It has led me to wrap up my practice. I think of the architect as someone who sees what is poetic in a place and transposes the emotions it has evoked. Yet, he must also be a realist, as architecture aims at creating places for people, where people will be able to luxuriate.

Designing my parents’ house allowed me to confirm at a micro scale the intimate link between one’s personal bond with the landscape and how a building will faithfully render its inhabitants’ emotions.

INT: Have your childhood memories influenced on your relationship to landscapes and how you’ve perceived the users’ needs?

GS: Of course. It is a rare occurrence that one’s poetic outlook on a place is intertwined with personal memories. Still, I stepped back as I do for my other projects – and my collaborators did not know the place. We followed our usual procedure: met the people, saw the place and translated the feelings it inspires.

It amounted to a discovery of the place and the people we work for. Within a limited budget, we had to stick to the essentials in conveying the timeless value of the place.

INT: In the case of your parents’ house, what did this value amount to?

GS: To me, it synthesized the classic image of the Bas-du-Fleuve landscapes, all plains with small granite mounds, Monadnocks, arising here and there. Farm buildings appear like strange objects disrupting the plane uniformity. I wanted to render the personality of these buildings looking like worn-out barns, beaten out of shape and colour by the icy climates.

For my parents, I reinterpreted a Bas-du-Fleuve gabled house [the lower St. Lawrence], misshaping it asymmetrically (with the roof overhanging on one single side). It emulates the incredible barns in this area, always looking on the verge of crumbling… They span time as if their architecture had frozen it.

INT: And what materials have you decided on to enhance the regional architecture?

GS: The harsh climate in the area changes buildings into a dark-grey colour. So, I chose a very thin metallic sheet for the roof, similar to the metal sheets they use in Bas-du-Fleuve, and walls made of black-painted boards.

From a distance, the spaces between materials and the angles are blurred, so the house changes into a mere abstraction, almost like a carved mineral dropped onto a eld. With snow, it really becomes black on white, an object that seems to merge with its shadow into abstraction.

Inside, all is painted white, including the veranda enclosed by a window screen, as if light was entirely contained within the object. Through such a contrast between the monochromatic exterior envelope and the inside luminosity, the house becomes an abstraction, the idea of the house itself.

The stone chimney, even older than the burnt down the house, lives a third life as it is integrated to the house annex.

INT: And, what about the interior architecture?

GS: The whole purpose of the place is to welcome light. We therefore used basic materials, wooden floors and plaster walls, free of the decorative frills induced by consumer society.

Fenestration has been designed according to a specific relationship with the landscape. In the living room, windows opening upon the whole height of the wall invite the landscape inside.

The general plan is that of the traditional Québécois house. I merely incorporated the annex by “folding” the roof, and organized the building around the veranda to open it on the outside. I wanted, with this project, to create a transition between the classic Québécois house and its contemporary version, without flamboyance, first and foremost to make a home for my parents in total harmony with our memories of the place.

Architect of Emotions

What do we take away from these interview series? Gilles Saucier draws and builds emotions! This was true in 2009, it was still true in 2017 when Stéphan Bureau of Radio-Canada spoke with the architect on this subject.

Listen to the podcast… here

Visit the web site of

Saucier+Perrotte Architects